Reflections on Khora & Reflections on Mary as Khora, “Container of the Uncontainable” — ἡ Χώρα του Ἀχώρητου and Jesus as Khora, “Dwelling Place of the Living”

(a seminarian reflection paper prepared for Pastoral Theology 10; Prof. Amy Lamborn, instructor; The General Theological Seminary, Michaelmas 2011)

I. Khora as Space; Khora as Other

“We have no space of our own except as it is defined in relationship to other spaces, the multiple and interpenetrating spaces of our unconscious life, our life together in society and our life in relation to Being itself, to what we call God.”[1]

The entry for “Χώρα: chora, choras” in Thayers Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament points to three meanings: 1) the space lying between two places or limits; 2) a region or country, i.e. a tract of land; and 3) land which is plowed or cultivated. The verb deriving from the same root, “cwre÷w: choœreoœ, choœroœ” carries these meanings: 1) to leave a space (which may be occupied or filled by another); to make room, give place, yield; to retire; to turn oneself; 2) to go forward, advance, proceed; to make progress, gain ground, succeed: 3) to have space or room for receiving or holding something; to receive with the mind, to understand; to be ready to receive, keep in mind, and practice: to receive one into one’s heart, make room for one in one’s heart.

Shades of all these meanings are reflected in the use of the term khora by Plato and the Neo-Platonists (including the understanding in the cultures of Byzantium and the writings of the Christian mystics), contemporary psychoanalysts (e.g. Julia Kristeva and Slavoj Zizek), post-modern deconstructionists (e.g. Jacques Derrida and John Caputo) and Christian philosopher Richard Kearney. Oftentimes the various meanings and shades in the meaning of the term khora interact with each other in subtle word plays and double meanings. There are underlying paradoxical senses of both movement/stasis[2] and familiarity/strangeness (relationship) in many of the usages of khora as the various writers infuse the term with the subtleties of their own intentions.

Plato’s understanding and application of khora

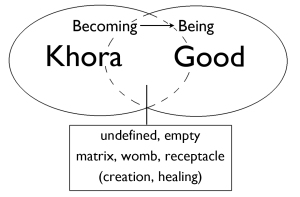

Plato’s dialogue the Timaeus is about the creation of the universe and the creation of man. Creation is described as a process of transition, the movement through becoming into the image (eikon) of Being. Plato’s khora is an empty “placeless place from which everything that is derives.”[3] It is paired with the Good, its polar opposite. Khora differs from the Good “in that it is not a fullness of presence and light but a dark bottomless ‘abyss’,”[4] but together they underlie a procreative gap.

Khora “is the receptacle and, as it were, the nurse of all becoming and change … [Because khora] is to receive in itself every kind of character [it] must be devoid of all character . . . Therefore we must not call [khora] the mother and receptacle of visible and sensible things either earth or air or fire or water… but we shall not be wrong if we describe it as invisible and formless, all embracing, possessed in a most puzzling way of intelligibility, yet very hard to grasp.”[5]

The Christian Neo-Platonistic understanding and application of khora

The writers of the New Testament scriptures and the early church fathers adopted and adapted Plato’s juxtaposition of the “Good beyond being”[6] and “khora before being” in the Christian apophatic theologies of transcendence and immanence – transcendent, unknowable God and immanent, kenotic khora. As we participate in both, the space in which we dwell is located in the gap in between, and in that spatial and temporal gap a creative, transformative movement from becoming to Being occurs.

The polarity between God and khora plays out in the Christian world in the polarities between a Hellenistic and a Hebraic understanding of God[7], between a hypostatic sur-real and an ecstatic sub-real experience of God[8] and in the tensions held between the Alexandrian and Antiochene schools in the deliberations of the early church councils.

The language of the Cappadocian Fathers often resembles Plato’s. Gregory of Nazianzus (4th century) defines Incarnation as the space chôrêtò kaì achôrêtò, meaning “that which occupies space, and does not occupy space,” an apophatic and paradoxical space both visible and invisible, present and absent.[9]

The patristic metaphor of the Trinity as perichoresis pictures the three Persons dancing around an empty space (khora).

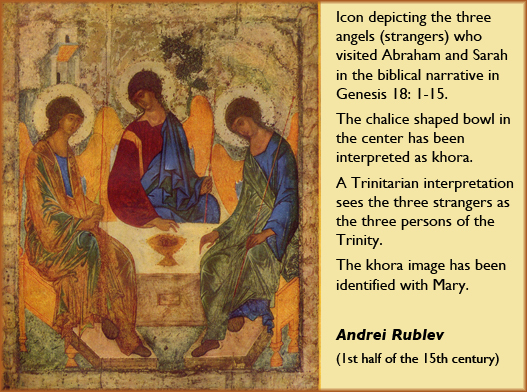

This image is a “sacred milieu of mutual withdrawal, letting be, love – three persons who would collapse into indifference and indifferentiation were it not for that free feminine spacing opening up between them: an Open that holds them at once together and apart.”[10] The concept of perichoresis, attributed to John of Damascus, was formulated in the 7th and 8th centuries to explain the eternal dynamic relationship between the persons of the Trinity. The famous 14th century Rublev icon (see page 1) correlates this relational basis of the persons of the Christian Trinity to the story of the three divine strangers who bring the promise of a son to Abraham and Sarah; the chalice-like form in the icon is the khora image.

The Psycholanalytic Khora: Maternal matrix

Philosopher/psychoanalysts Julia Kristeva and Slavoj Zizkek borrow Plato’s concept of khora as matrix – the space of early psychological movement toward differentiation and self-identity, yet still a space in which “elements are without identity and without reason.”[11] Kristeva cites the need in early developmental stages for the emerging “ego-self” of the child (up to about six months old) to “abject” the maternal khora. This breaking away from the maternal in the space of khora is a paradoxical movement, with and against the khora – a sense of simultaneous dependency and pushing away. The result is that “khora is no more than the place where the subject is both generated and negated, the place where his unity succumbs before the process of charges and stases that produce him.”[12]

The Khora of Deconstruction

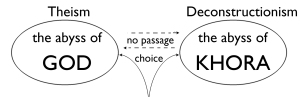

The postmodern, deconstructionist philosopher Jacques Derrida addresses khora as without being in that it “eludes all anthropo-theological schemes, all history, all revelation, all truth”[13] For Derrida, khora is the space of de-construction – khora as an alternative to theology.

John Caputo follows much of Derrida’s thinking. Building on Plato (“Khora is neither present nor absent, active nor passive, the Good nor evil, living nor nonliving” – Timaeus) Caputo states that “khora is “neither theomorphic nor anthropomorphic – but rather atheological and nonhuman – khora is not even a receptacle, which would also be something that is itself inscribed within it.”[14]

Set against the apophatic theology of the Neo-Platonists (exemplified by Dionysius) who emphasized the unknowable transcendence of God, the deconstructionists seem to prefer the unknowable immanence of khora, rejecting unconditionally, however, the immanence that is the foundation of the Christian understanding of incarnation. John Manoussakis observes that the deconstructionists’ “fear of immanence costs them the loss of transcendence.”[15]

The Khora of Kearney’s “Third Way”

On the tail of the deconstructionist argument and the positions of other theological and philosophical post-moderns who preach, in one form or another, the “death of God” or “the death of God as we have known God,” we face the question “What comes after God?” Richard Kearney suggests a “third way” – a path that leads beyond absolutes beyond both “dogmatic theism and militant atheism.” He envisions Ana-theism – God after God, a return to God, an opening into God after God’s perceived absence.[16]

Anatheism values critical atheism as an important corrective and catalyst in an ever-evolving “faith beyond faith” – faith that is elevated with each cycle of returning to God after a period of perceived absence. In this understanding of human relationship with God, God and khora stand not in opposition to each other, but as partners in dialogue.[17]

Anatheism honors the sacramentality of the connection between the holiness of the sacred and the holiness of the secular. Kearney points to four “divine descents into the empty space of the ordinary: creation, exodus/wilderness, incarnation and death/resurrection” – each one calling forth and revealing new life out of the old – each arising from the depths of khora.[18]

With the consideration of Mary as “Container of the Uncontainable” we are reflecting on the divine descent – incarnation.

II. Mary as Khora: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; Be it unto me ”

“Judeo-Christian tradition describes this [khora][19] as incarnate space; it is the space of the person that God enters and fills, rearranging human contours, making new things possible. . . . Here the question of value takes on shape. Here we ask not only who we are, and who we are in relation to others, but also who we are for. Where and to what do we devote ourselves? For what meaning, for what love, do we empty our space to make room for new being?”[20]

The Christian Khora, Incarnation and God’s Space in the World

At the foundation of the Christian faith is the conviction that God, who has always been present among God’s people Israel is gathered together and present to us in the person of Jesus Christ, Immanuel, “God with us.” Jesus is at once, in human form the Temple, the Word spoken by all the prophets and the Torah. Jesus is the presence of God to us, as the Israelites had previously known God present and contained in the Ark of the Covenant, the Tabernacle, the sacred vessels of the Temple, the Temple itself and the fortified walled city of Jerusalem. All these symbolic images become God’s “space” in the world, a holding space for God and God’s creative activity in the world – but not synonymous with the uncontainable God. These spaces share the characteristics of khora.

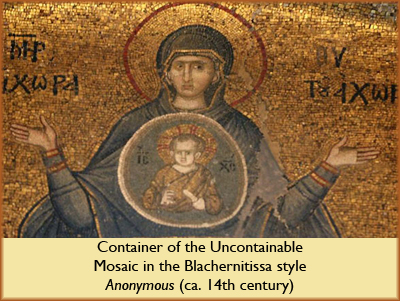

With the angel’s annunciation to Mary, her fiat and the overshadowing of the Holy Spirit, she becomes the “bearer of God,” the “replication of the khora in the body.”[21] God’s space in the world becomes a person; Mary becomes the khora akhoraton, the “container of the uncontainable”.[22] As in the Platonic understanding of khora, Mary receives the entire divine person of Christ within her body without appropriating it into herself.[23]

While it seems logical and natural to associate this imagery with pregnancy and motherhood, especially remembering Plato’s metaphors in the Timaeus of khora as matrix, mother and nurse, Caputo and Derrida remind us that khora is not a nurturing, motherly space. Thus the image of Mary as khora points to the paradoxical charater of khora described by Kristeva.[24]

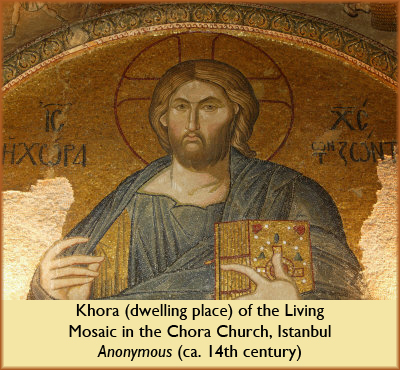

The earliest designation of Mary as khora akhoraton can be traced to the anonymous 5th or 6th century Akathistos Hymnos in the Eastern Church, and the inscription ἡ Χώρα του Ἀχώρητου is characteristic of a type of Byzantine icon on which Christ is portrayed in an egg-shaped container giving the visual image of Christ as contained within Mary’s womb. Concurrently and paradoxically, Mary is the khora who opens the heart of the divine. (See above for a reproduction of the most famous icon of this type located in the monastery of Chora outside Istanbul/Constantinople.[25])

Mary, Khora and Anatheism

Mary’s answer to the Annunciation was an anatheist moment.[26] We can easily imagine that the encounter with the stranger who appeared to Mary in the name of God brought fear and confusion to her mind and spirit. That she was troubled and pondered as she considered the suggestion of the stranger indicates that it was her choice to acquiesce as her fear turned into consent. Her acquiescence was further transformed into faith filled, prophetic jubilance in her Magnificat.

III. Jesus as Khora: “And the Word was made flesh and dwelled among us”

“We get to God by enlarging, opening our ego-containers, letting God get to us, pouring out of ourselves into the lives of others, and being filled in our emptiness by an accrual of being that enters from God’s side. . . Saving space is where we confront the largeness of Being, paradoxically, in the small container of our self . . . In such experience of saving space we have intimations of the space of resurrection.”[27]

Opposite and facing the mosaic of Mary in the Chora monastery is another khora icon, this one the image of Christ bearing the inscription “khora (dwelling place) of the living,” the khora as the receptacle of all humanity, all creation “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.”[28] The positioning of the two khora images seems to recall the Platonic interplay between khora and the Good and suggests that spaces – and perhaps all sorts of beings, groups and societies – are defined in relationship to other spaces, beings, groups and societies . . . and our life [is defined] in relation to Being itself, to what we call God.”[29]

********************

********************

********************

FAVORITE KHORA QUOTES

“But let me tell you that to approach the stranger

Is to invite the unexpected, release a new force,

Or let the genie out of the bottle.

It is to start a train of events

Beyond your control . . .

(a character in T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party)

——————————

Without khora, there is:

- no faith, because then God would have plainly and unambiguously revealed Godself, without any possible confusion

- triumphalism, dogmatism, the illusion that we have been granted a secret access to the Secret (these are the illusions that makes religion dangerous, that “fires the fundamentalist religious hallucination”)

- no “impossible”, no poetics of the possible, nothing to drive us to the impossible

- no hoping against hope, hoping when hope is impossible

- no demands of the impossible – “which elicits faith, hope and charity”

(adapted from John T. Caputo, “Abyssus Abyssum Invocat: A Response to Kearney”)

——————————

Khora is the “devil that justice demands we give his due . . .”

(John T. Caputo, “Abyssus Abyssum Invocat: A Response to Kearney”)

——————————

God is nothing in anything because He is “all thing in all things” (1 Cor. 15:28)

“Although He is nowhere, there is nowhere that He is Not” (Enneads V, 5, 8:24-25)

(quoted by John Panteleimon Manoussakis in “Prelude: Figures of Silence” from Godafter Metaphysics: A Theological Aesthetic)

********************

********************

********************

NOTES:

[1] Ann Belford Ulanov, “Being and Space,” Union Seminary Quarterly Review XXXIII No. 1 (Fall 1977), 12.

[2] Charles Bigger notes both a static and a dynamic component: static in the sense of one person being “in” the other, occupying the same space as the other, filling the other with its presence; and dynamic in the sense of the interpenetration and permeation of one person with/in the other. (Between Chora and the Good: Metaphor’s Metaphysical Neighborhood, Perspectives in Continental Philosophy. New York: Fordham University Press, 2004, pg. 102.) Following John Sallis, Nicoletta Isar observes that the paradox of movement/stasis results in “the unstable ground of play between presence and absence” and that the presence of khora might only be seen in its movement. Therefore khora could be called a “motional presence.” (“Chôra: Tracing the Presence.” Review of European Studies 1, no. 1 (June 2009): 39 – 50. Accessed November 21, 2011. http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/res/article/ view/2467, pg. 40-41.)

[3] Richard Kearney, “Chapter 9: God or Khora,” in Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness (London/New York: Routledge, 2003), page 193.

[4] Ibid. 199.

[5] Plato in Timaeus 49-51. (Quoted in Kearney, Strangers, Gods and Monsters, 194.)

[6] Denys the Areopagite (6th century) identified the Platonic Good as the Christian God of love, the God of 1 John 4:8 – “God is love.” As a verb “love” requires an object and in so doing defines and reveals subject and object in relationship.

[7] John Panteleimon Manoussakis, “Figures of Silence,” in God after Metaphysics: A Theological Aesthetic (Indiana Series in the Philosophy of Religion) (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007), 90.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Nicoletta Isar, “Chôra: Tracing the Presence,” Review of European Studies 1, no. 1 (June 2009): 42, accessed November 21, 2011, http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/ index.php/res/article/view/2467.

[10] Richard Kearney, “Epiphanies of the Everyday’ Toward a Micro-Eschatology,” in After God: Richard Kearney and the religious turn in continental philosophy, ed. John Panteleimon Manoussakis (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006), 10.

[11] Julia Kristeva, quoted in Kearney, “God or Khora,” 195.

[12] Kearney, “God or Khora,” 196.

[13] Jacques Derrida in On the Name, quoted by Kearney, “God or Khora,” 199.

[14] John D. Caputo in The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida, quoted by Kearney, “God or Khora,” 199. This statement sets Caputo’s khora in direct opposition to the Christian view of Jesus as both divine and human as well as the Christian concept of Mary as “receptacle” or “container.”

[15] Manoussakis, 90. Reflecting the Christian understanding of God who reveals Him/Herself as both immanent and transcendent, Eric Perl has written that “transcendence which is not immanence is not true transcendence, but mere otherness.” (Perl quoted by Manoussakes. Perl: “Signifying Nothing: Being as Sign in Neoplatonism and Derrida.” In Neoplatonism and Contemporary Thought, vol. 2, ed. Harris R. Baine, 125-151. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002.)

[16] Richard Kearney, Anatheism: Returning to God After God (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 3.

[17] Kearney, “God or Khora,” 194.

[18] Kearney, “Epiphanies of the Everyday,” 10.

[19] (Note: The link between khora and incarnate space in the context of Ulanov’s article is my correlation – my suggestion, thus the insersion of “khora” in the quotation of Ulanov. JH)

[20] Ulanov, “Being and Space,” 19 – 20.

[21] John Sallis, quoted in Isar, 40.

[22] An alternative translation is “receptacle of the un-receivable. (Manoussakis, 92.)

[23] Manoussakis, 92.

[24] The understanding of Mary as the human mother of Jesus is doctrinally important to Christians because it is Mary who imparts her humanity to Jesus.

[25] The placement of the khora mosaics in the space of the interior of the church allowing their interaction with OT mosaic scenes that prefigure the Incarnation creates a statement of the theology of the Christian khora. The Virgin khora is strategically positioned at the entrance of the church.

[26] Richard Kearney, Anatheism: Returning to God After God, 8.

[27] Ulanov, “Being and Space,” 21.

[28] The four “Chalcedonian adverbs” from the 5th century definition of Christ as one person in two natures.

[29] Ulanov, 12. (See opening quotation, page 1.)

References

Becker, Gerhold K. The Moral Status Of Personal Perspectives on Bioethics. Amsterdam: Rodopi Bv Editions, 2000.

Bigger, Charles P. Between Chora and the Good: Metaphor’s Metaphysical Neighborhood (Perspectives in Continental Philosophy). New York: Fordham University Press, 2004.

Burkey, John. “A Review of Richard Kearney’s Anatheism: Returning to God after God.'” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 10, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 160 – 166.

Caputo, John T. “Abyssus Abyssum Invocat: A Response to Kearney.” In A Passion for the Impossible: John D. Caputo in Focus, edited by Mark Dooley, 123 – 127. Albany, NY: State Univ. of NY Press, 2003.

Isar, Nicoletta. “Chôra: Tracing the Presence.” Review of European Studies 1, no. 1 (June 2009): 39 – 50. Accessed November 21, 2011. http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/res/article/ view/2467.

Jenson, Robert W. “A Space for God.” In Mary, Mother of God, 49 – 57. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2004.

Kearney, Richard. Anatheism: Returning to God After God . New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

________________. “Epiphanies of the Everyday: Toward a Micro-Eschatology.” In After God: Richard Kearney and the religious turn in continental philosophy, 3 – 20. New York: Fordham University Press, 2006.

________________. “Chapter 9: God or Khora.” In Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness, 190 – 211. London/New York: Routledge, 2003.

Manoussakis, John Panteleimon. “Prelude: Figures of Silence.” In God after Metaphysics: A Theological Aesthetic (Indiana Series in the Philosophy of Religion), 75 – 92. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Ousterhout, Robert. “The Virgin of the Chora: An Image and Its Context.” In The Sacred Image East and West (Illinois Byzantine Studies), 91 – 104. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

________________. Pictorial Decoration: Sequence, Iconography and Style Based on the research of Professor Robert Ousterhout, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/wallach/exhibitions/ Byzantium/html/building_icon.html.

Ulanov, Ann Belford. “Being and Space.” Union Seminary Quarterly Review XXXIII No. 1 (Fall 1977): 11 – 22.

________________. Finding Space: Winnicott, God, and Psychic Reality. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2001.